Journey to a Nonsurgical Sterilant

By Dick Anderson

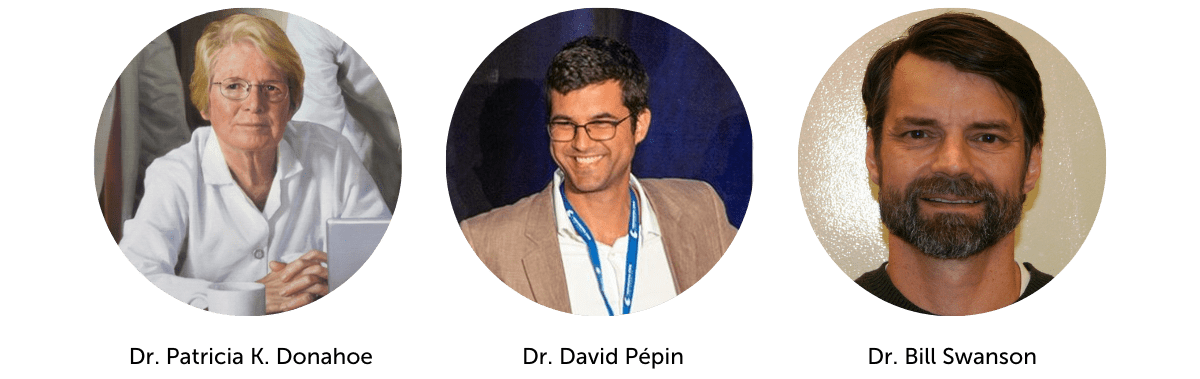

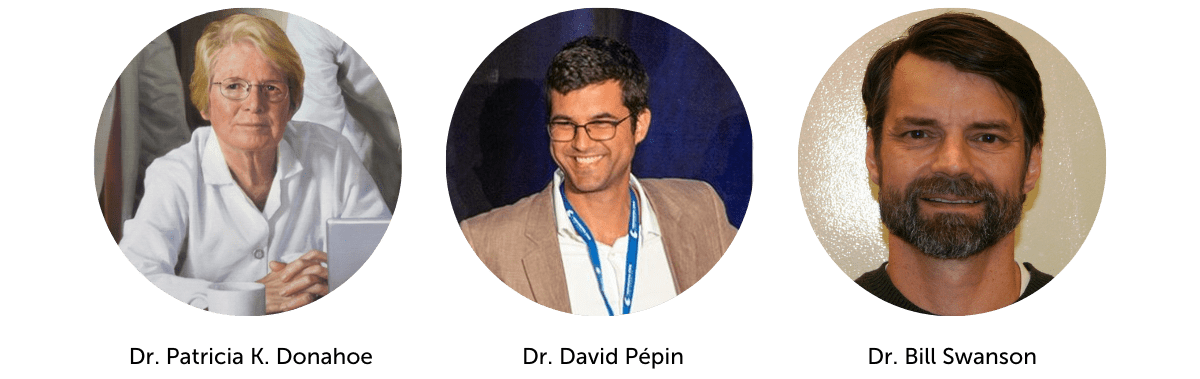

After nearly a decade in development, a single-dose, nonsurgical sterilant for companion animals has yielded promising results. In a newly published study in Nature Communications, lead author Dr. Lindsey Vansandt, a theriogenologist at the Cincinnati Zoo’s Carl H. Lindner Jr. Family Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife, details the findings of a team of scientists working on a new gene therapy treatment with an ovarian hormone to inhibit ovulation and induce durable contraception in the female cat. The work is led by principal investigators Dr. David Pépin, associate professor of surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Dr. Bill Swanson, the Cincinnati Zoo’s director of animal research.

Initially working in the lab of Dr. Patricia K. Donahoe, director of pediatric surgical research laboratories and chief emerita of pediatric surgical services at Massachusetts General Hospital, Pépin was studying the biochemistry of the ovarian Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH, also known as Müllerian inhibiting substance, or MIS), in the context of ovarian cancer about a decade ago. That’s when a chance discovery in immunosuppressed mice led the researchers to develop a gene therapy strategy to deliver an optimized feline AMH transgene for contraception in the domestic cat.

“I think it’s a case where we had a solution looking for a problem,” Pépin says. “We had something extremely effective. Maybe it was not so useful for humans. So, we thought, where can we get the most benefit from this discovery—where can this do some good?”

Thanks to a colleague at Massachusetts General Hospital, Pépin and his team learned about the Michelson Prize & Grants in Reproductive Biology, a $75-million initiative launched by the Michelson Found Animals Foundation in 2008 to create a nonsurgical sterilant for cats and dogs to eliminate shelter euthanasia of healthy, adoptable companion animals and reduce populations of free-roaming cats and dogs.

“In many parts of the United States and around the world, you’ll see dogs just wandering down the street, and invariably, they are not neutered or spayed,” says Dr. Gary K. Michelson, founder and co-chair of Michelson Philanthropies, which hosts the Michelson Prize & Grants program. “It’s very expensive and logistically difficult to have these animals undergo surgeries that require anesthesia. Even in America, many families don’t have the resources to have their animals spayed and neutered.”

According to the Best Friends Animal Society, about 4.4 million cats and dogs entered U.S. shelters in 2022. Many of those result from unplanned litters, and millions more cats are living outside with inadequate care. If there was a means of dramatically reducing unwanted reproduction, Dr. Michelson reasoned, “Every municipal animal shelter could successfully find a live outcome for every healthy dog and cat. That is the holy grail.”

When the Michelson Prize & Grants program was first announced in 2008, “Dr. Michelson stipulated that he wanted a sterilant that didn’t require surgery, something that would suppress hormonal activity in dogs and cats,” Swanson says.

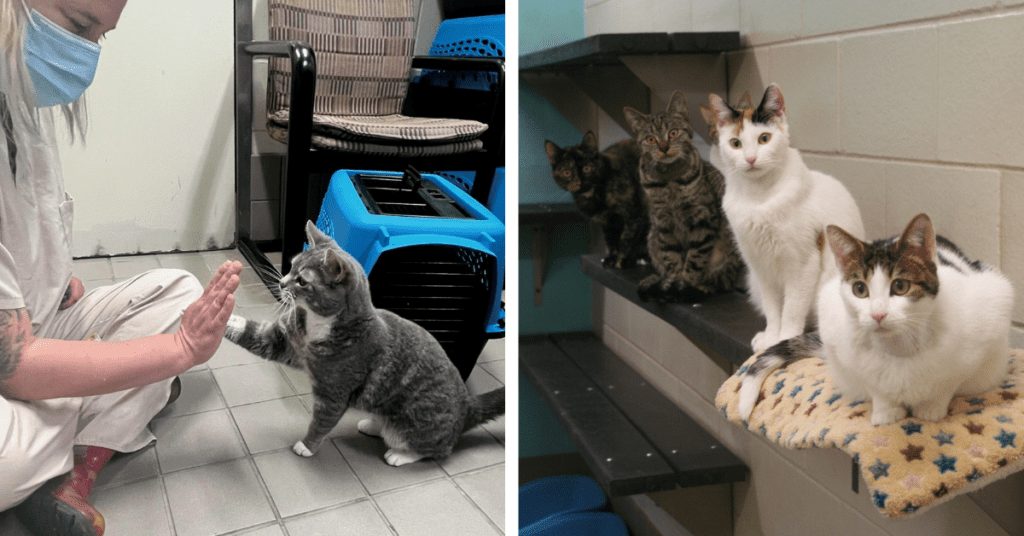

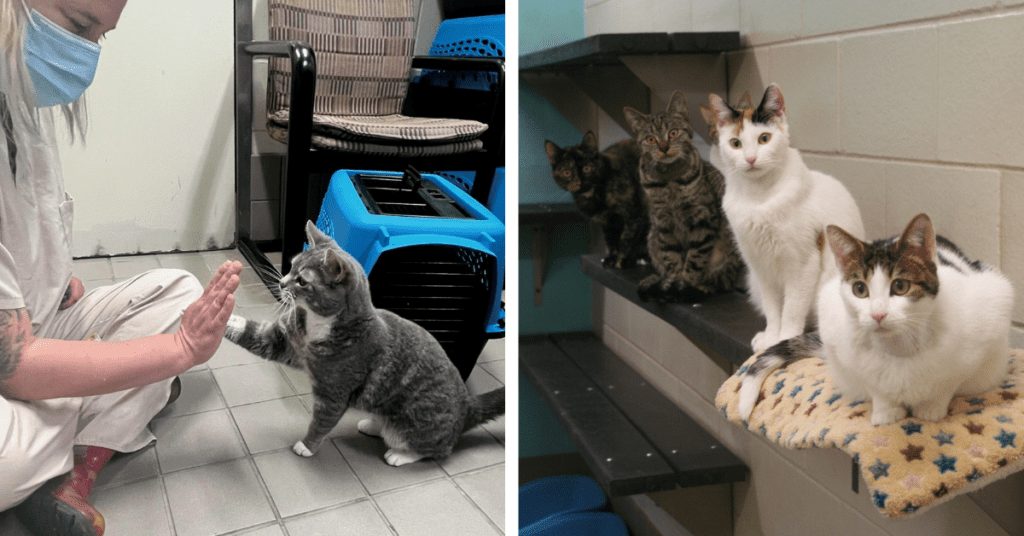

Pointing toward the potential breakthrough of a sterilant for female cats, he notes, “The main metric we’re looking at is reproduction: Are they breeding and reproducing? And those data are very solid and exciting. We’re also monitoring reproductive hormones in these cats and looking at their behavior. The ultimate goal is keeping cats from reproducing. And we’ve shown clearly that we can do that safely and effectively, with absolutely no adverse effects observed in any of the treated cats, all of which are either eligible for adoption or already in loving adoptive homes.”

“The results in the cats have been amazing.” Donahoe says. “The care in the design and the delivery and the interpretation of this has been really outstanding. I think this paper will make a real mark on the field of reproduction.”

Over the last 15 years, the Michelson Prize & Grants program has funded 41 projects totaling more than $19 million in committed funds for this specific area of research. “We have figured out a lot of things that don’t work, which in itself is progress,” says Becky Cyr, program manager of the Michelson Prize & Grants program since 2012. “When this program started, our scientific advisory board was interested in hearing any idea with scientific merit. And we have funded a broad range of approaches over the years.”

“There’s not a lot of funding in this space to begin with,” says Dr. Thomas Conlon, chief scientific officer of Michelson Philanthropies and Michelson Found Animals. “The work that we have funded, the peer-reviewed publications that grantees have put out, and the presentations that they’ve given at conferences are adding to the scientific literature in this area of research. That wouldn’t be occurring without Dr. Michelson’s funding.”

The road to a nonsurgical sterilant can be traced back to Dr. Michelson founding the Michelson Found Animals Foundation in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The foundation’s success in developing a national microchipping network caught the eye of Joyce Briggs, president of the nascent Alliance for Contraception in Cats and Dogs (ACC&D), who approached Dr. Michelson about funding a prize to advance the development of nonsurgical sterilant for cats and dogs.

“Cats are really good at reproducing,” says Briggs, who began volunteering in animal shelters as a teenager. “They are predominantly induced ovulators, which means that the act of mating actually causes ovulation. They continually cycle until they get pregnant. It is very challenging to interfere with that.” (Dogs are very different from cats, she notes: They usually cycle once or twice a year.) “We still have an overpopulation issue with cats in many areas of this country. And in almost every area, there are issues with free-roaming cats that are very hard to get ahead of.”

In 1999, Briggs became executive director of PetSmart Charities, the nonprofit arm of the world’s largest pet supplies retailer. Within a couple of years, Briggs started to see a trickle of applications from scientists interested in pursuing nonsurgical spay/neuter technologies. “I did not have the scientific background to evaluate the potential of these technologies, but as a funder, I desperately wanted our spay neuter grants to better address the huge need. I was very interested in advancing the technologies,” she says.

Around 2000, Briggs was a founding member of Animal Grantmakers, which pulled together a “summit of sorts” of a couple of dozen grantmakers and scientists to foster a greater understanding of the potential of nonsurgical sterilization. At that same summit, Briggs met three scientists from the Auburn University and Virginia Tech veterinary schools who had just formed the Alliance for Contraception in Cats and Dogs (ACC&D), which bridges the animal welfare, scientific, veterinary, and pharmaceutical communities with the shared goal of expanding options for controlling feline and canine reproduction.

After Briggs became president of the nonprofit ACC&D in 2006, she and her board of directors began to actively seek out funding toward the development of science-based nonsurgical spay/neuter procedures. Before long, someone suggested that she should consider approaching Dr. Michelson with the idea for the prize, and it made sense to Briggs: “Gary’s scientifically minded; he’s from the medical establishment; and he believes in innovation around solving things,” she recalls thinking. “What better than a scientifically-based medical intervention that could be a game changer for this field? It was a really nice match for him.”

Dr. Michelson was receptive to Briggs’ “bold ask” of creating a $10 million prize, “but it wasn’t audacious enough,” he recalls. “It needed a bigger prize.” So, he upped the ante to $25 million, and responded to the ACC&D Board’s follow-up request that he also provide grant funds, adding $50 million in grant money to underwrite the research. “In essence, there was zero research going on in this field,” he says. “Unless we were willing to fund the research ourselves, nothing would happen.”

When the Michelson Prize & Grants program was announced, it made headlines nationally. “Saturday Night Live said the cats and dogs got together and put up $75 million to have me fixed,” he recalls with a laugh. “In the beginning, we were funding lots of divergent hypotheses about how you might achieve this.”

Soon after Dr. Shirley Johnston was named Michelson Found Animals’ director of scientific research in 2009 (a position she would hold until 2016), one of the first things she did was form MFA’s scientific advisory board, which has been the brain trust and driving force of the Michelson Prize & Grants program from day one. “In the first few years, we processed tons of letters of intent and grant applications,” Cyr says.

David Pépin went through the traditional channels of submitting a letter of intent and grant application in 2014. “He was doing some research at the time where a side effect of a treatment that he was working on happened to cause infertility in rodents—and he thought there might be other applications for this,” Cyr says.

“I joined Pat Donahoe’s lab as a postdoc initially to work on ovarian cancer and the biochemistry of AMH—how to make it and how to use it in the context of ovarian cancer,” recalls Pépin. He did his Ph.D. at the University of Ottawa studying ovarian function—how the ovary works—and folliculogenesis, which is the growth of follicles that leads to ovulation.

For Pat Donahoe, the pet overpopulation problem was made “very evident” at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, where hundreds of stray dogs were culled before the games, igniting a global outrage. “When the athletes arrived in the Olympic Village, they were surrounded by feral cats and many feral dogs,” she recalls. “It became quite obvious that this problem is a scale of magnitude that we don’t even conceive of.”

“As a pediatric surgeon, I was extremely interested in reproduction and the birth defects that occur with reproduction,” says Donahoe, who has worked her entire career at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Harvard Medical School. She was spending a lot of time reconstructing children who were born with intersex abnormalities and closely followed the AMH work being done by Dr. Jean Wilson, an internationally recognized endocrinologist and professor of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“We were working on AMH because it had this tremendous effect in the male embryo of wiping out the Müllerian ducts, which would otherwise give rise to the female reproductive system,” Donahoe explains. “We had two concepts in mind. One is that this was a very powerful inhibitor. And if it’s an inhibitor, could we use it to inhibit tumors of the Müllerian ducts and the most prominent of which is ovarian cancer and all ovarian cancers recapitulate the developmental program or the development of the Müllerian ducts. So, we started very slowly looking at designing a bioassay for AMH, then learning to purify it, then cloning the gene for it, which we did with Biogen Corporation.”

It was at that stage that Pépin came to the lab as a postdoc. “He was a godsend at that point because we had cloned the gene, and yet the purification schemes were very, very difficult,” Donahoe says. “David worked on changing the constructs to make them more potent and to improve our ability to sequence and purify them. And David was able to change the construct, change the gene so it was easier to produce and cleaner and almost 100 percent purified.”

“Because of my training on ovarian physiology, I was also interested in looking at what the effect on the ovary was, and that’s how we made that discovery,” Pépin says. “At the outset, we were trying to treat ovarian cancer. It was already known that AMH was an ovarian hormone that may regulate ovarian follicles. But what we found is that it was much more potent than anticipated and actually completely shut down the ovary.”

As they thought about the applications for this discovery, “The most obvious one, if you’re shutting down ovarian function, is contraception, and we were looking at different funding opportunities that pursue that,” Pépin continues. Caroline Coletti, program manager at Massachusetts General Hospital, found the Michelson Prize website and showed it to Pépin.

“I thought, ‘Wow, that’s very interesting,’” he recalls. “As part of the grant, what we wanted to do is clone both the dog and cat AMH genes. So, we needed to identify people that would help us with both of these.” Pépin reached out to Dr. Guangping Gao, director of Horae Gene Therapy Center and Viral Vector Core at the University of Massachusetts and maker of all the vectors for these studies, and they submitted a proposal together to the Michelson Prize & Grants program.

“Our contact with Guangping Gao was serendipitous and really terrific because they had the knowhow of making these adeno-associated viruses and scaling them up,” Donahoe says. “They’ve been very flexible and a dream to work with.”

The maturation of the gene therapy field has been key to the team’s research, Swanson notes. “Twenty years ago, we probably wouldn’t be proposing to do anything like this, even though gene therapy was active then.” (On the subject of gene therapy, he adds, “We’re not genetically modifying these individual animals. This is producing a protein over the life of the animal which will shut down reproduction. It has no effect on the animal’s DNA.”)

Dating back to his work with the Austin Humane Society in the early 1980s, Swanson has been wrestling with the overpopulation of dogs and cats in the United States. “Most of my career has been focused on trying to conserve endangered cat populations—kind of the opposite of keeping them from breeding,” says Swanson, who joined the Cincinnati Zoo in 1997. “We want these endangered cats to breed, and we want to be able to keep their populations viable.”

Along with completing his Ph.D. research at Louisiana State University focused on domestic cat reproduction, Swanson worked at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, which used the domestic cat as a reproductive research model for endangered cat populations. His mentor at the Smithsonian, wildlife biologist Dr. David Wildt, recruited him to the scientific advisory board for the Michelson Prize & Grants program about a decade ago.

Swanson first met Donahoe and Pépin at a meeting in California for the Michelson Found Animals Foundation. “I hadn’t been on the board that long at that point, and they had come out for a grantee meeting,” he recalls. “The work David and Pat were doing and proposed to do looked promising based on the mouse data.”

Over time, Swanson’s role evolved from being an adviser to a collaborator on Pépin and Donahoe’s project. “They needed someone with expertise on cat reproduction to take this from the mouse model to the cat as an endpoint,” he says of Pépin and Donahoe. “Because we study cats as a model for endangered cats in my facility at the zoo, we work with them all the time. It was a really good fit with the project that David and Pat were developing to see if this inhibitory protein-anti-Müllerian hormone-would work in inhibiting reproduction in domestic cats.”

“Our colony has about 50 domestic cats now—we’ve had as many as 100—and most of those are here because of the project that we’re doing with David and Pat,” he adds. (In November 2015, the Swanson lab worked on a study sponsored by ACC&D to evaluate the potential of a vaccine named GonaCon as a long-term contraceptive for female cats.) “We’re in our third study now with David and Pat, and we have plans for more studies as we go on. The results of the first two studies were impactful and promising for what we’re trying to achieve.”

As a conservation biologist and a veterinarian, “I look at this as an animal welfare issue,” Swanson says. “Because these stray dogs and cats live outdoors, they can have pretty traumatic lives. A lot of these animals get infectious diseases or get hit by automobiles.”

In addition, “Cat predation is a major source of mortality in wild birds,” notes Jenny Gainer, Swanson’s colleague and curator of birds and African animals at the Cincinnati Zoo. “Controlling and reducing the population of free-roaming cats will make a major difference for declining songbird populations.”

When would a sterilant like this actually be available for use? “Just like any drug for humans, it has to go through regulatory approval for use in companion animals,” Pépin says. “So that means doing clinical trials. That means going through the FDA, and that’s a multi-year process. In some ways, we’re lucky that we can do experiments in the target species, which is not usually the case in humans,” he adds. “We already have data on cats. So now it’s just a matter of demonstrating safety, proving effectiveness in a larger population of female cats, and developing a cost-effective manufacturing process.”

Michelson Found Animals is scheduled to meet with the Center for Veterinary Medicine at the FDA to begin the regulatory approval process. “We’re going to discuss our pivotal study plans for the next few years,” Conlon says. “The FDA will provide guidance on whether they agree with our plan as well as review our study designs to establish safety and efficacy. We will also have to develop robust quality manufacturing and those processes will be reviewed by the FDA as well.” Any approval of a nonsurgical sterilant, domestically or abroad, is “years down the road,” he adds.

As the work progressed, Pépin is running a large group now as an independent investigator at the Harvard Medical School (where he was promoted to associate professor in 2021). “I have my own lab now that studies the ovary first and foremost,” he says.

Without the support of Michelson Found Animals, Pépin adds, “I guarantee this work would have never happened. Our interaction started as a more typical funder/grantee relationship. But as we’re getting closer to a product and real-life application it’s evolved into a different role. We’re in constant contact and more like a team working on it with a common objective.”

“I don’t think Dr. Michelson has ever denied any of our requests for funding,” adds Donahoe. “They’re very particular—they want everything spelled out in detail before they release their funds—but that’s our mantra as well.”

“The funding from Dr. Michelson has been transformational,” Swanson says. “There really wasn’t much being done in the field of dog and cat contraception until this funding source became available. Universities aren’t going to be doing the research if they can’t get the money to do it. Before the Michelson Prize & Grants Program, that probably would’ve been a dead end.”

Pépin discussed the study’s findings at the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy’s 26th annual meeting in Los Angeles on May 20 in a talk titled Use of a Gene Delivery Approach for Single Dose Lifetime Sterility in Female Cats: An Alternative to Spay. Pépin’s presentation was delivered during a four-hour symposium on gene therapies for companion animal health that was chaired by Conlon.

“This presentation and now the subsequent publication represents the breakthrough moment where we’re finally able to talk about all the Pépin data after having the intellectual property all locked up,” Conlon says. Any resulting product “has to be something that is cost effective to produce,” Dr. Michelson adds. “If it’s so expensive that we can’t produce it, then we really haven’t succeeded. We have to have a product that’s usable.”

In deploying the sterilant as a business model, the challenge may well be finding an intersection between those who can afford it and getting it at the lowest cost to the most in need. ACC&D has done some market analysis for Dr. Michelson on what the market size looks like for these target audiences. “While the hope is that this can be provided as affordably as possible to charitable initiatives for homeless animals and for people who have very little income for veterinary care, this is also a benefit for pet owners who would prefer something less invasive than surgery,” Briggs says. “The business model is important to us at ACC&D because a new tool is only as good as how well we’re able to deploy it in the field.”

“Having worked on spay/neuter for 30 years now, this is a legacy I want to leave behind,” she adds. The irony that a trio of surgeons and surgery researchers —Donahoe and Pépin, with the support of Dr. Michelson—may have succeeded in creating a nonsurgical sterilant is not lost on her: “I love that.”

“If everything that we’re doing fails—and I don’t think we’ll fail—there will always be another technology to be explored until we achieve our goal,” Dr. Michelson says. And if the prize criteria for either the cat or dog is met, he adds, “I’d be more than happy to write that check.”